*z”l=zichrono livracha, of blessed memory.

The following is a collection of memories about Rabbi Ben Zion Wacholder from his family, friends, colleagues, and students, as well as a collection of some documentation of his life and career.

Every contribution comes from someone who directly interacted with Rabbi Wacholder, and has been posted as received, without editing. As the family of a historian, we know well that individual memories vary about details such as times and dates (and a whole lot more). In spite of any minor discrepancies, collectively these memories provide a strong and consistent picture of Ben Zion Wacholder.

Please visit www.BenZionWacholder.net to read Rabbi Wacholder’s own memoirs.

We invite you to share your own memories Ben Zion Wacholder by sending them to BZWacholderMemories@gmail.com.

Contents

Family Memories

(1) Notes From a Granddaughter, by Tzipora Wacholder

(2) Sholom Wacholder’s talk at Ben Zion Wacholder’s Memorial Service in New York

(3) Hannah Katsman’s eulogy for her father Ben Zion Wacholder

Students, Colleagues, Neighbors, and Friends

(1) Rabbi Ned Soltz (Teaneck, NJ) remembers Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l

(2) David Maas, Ph. D., (Assistant Professor of Old Testament/Instructional Mentor Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary) remembers Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l

(3) Memories from Marty Abegg

(4) Memories from Timothy Clontz

(5) Memories from Rabbi Charles Arian (Norwich, CT), originally posted on Facebook

(6) “In memory of my teacher and mentor, Ben Zion Wacholder,” from Rabbi Gil Nativ, Congregation Magen Avraham

(7) Shabbat Pesach, a story from Rabbi David Wilfond

(8) Hesped for Rabbi Wacholder, from Rabbi Ed Boraz, Rabbi of the Dartmouth College Hillel

(9) Remembering Dr. Wacholer, from Rabbi Stephen J. Einstein

(10) A Memory From Akiva Wagschal

(11) Memories from Madeleine Isenberg, a Student ca. 1954

(12) Obituary by James Bowley Delivered to the HUC Board of Governors

(13) Thoughts from James Bowley nearing Ben Zion Wacholder’s First Yartzeit

Published Obituaries

(1) HUC-JIR Mourns Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l

(2) Remembering Rabbi Wacholder, professor emeritus of Talmud, Rabbinics at HUC-JIR, from The American Israelite

(3) An Obituary by Michael A. Meyer, Adolph S. Ochs Professor of Jewish History, HUC-JIR/Cincinnati

Other Documentation

(1) Record of Ben Zion Wacholder’s departure for South America

(2) Bibliography of works by Ben Zion Wacholder, from Pursuing the Text: Studies in Honor of Ben Zion Wacholder on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday

Family Memories

(1) Notes From a Granddaughter

By Tzipora Wacholder

My Zaidy:

You were a wonderful grandfather. You did so much for all of us and showered us with love and attention. You cared that we should think and learn and grow. You exemplified the phrase “lifelong learner” and were able to communicate that to all of your descendants.

I was happy to have introduced myself to you one last time. The conversation we had, each time I came to visit, replays in my head. Zaidy would grasp my hands firmly, and ask “Who is this?” I would say “This is Tzipora. David’s daughter.” You would call me your lovely granddaughter and tell me how much you love me.

Whenever we saw you, we would cuddle next to you and talk about our lives. Zaidy was always most eager to hear about our studies. “Do you like school?” he would ask, “What are you learning?” Then he would ask us incisive questions in order to deepen our understanding.

Occasionally he would teach us an interesting random fact. I remember him telling me about the beauty of prime numbers, and his delight in how many of the special numbers in Judaism are prime, such as 613, 13, and 7. He loved all kinds of knowledge and, even more, he loved sharing his knowledge with others. His enthusiasm was contagious.

Zaidy treated every person with tremendous respect. He did not discriminate between people by status, money, religion, or even age. Anyone he met was judged solely by their content. This enabled him to speak as easily to a child as to prominent academics.

Zaidy related to each person on their own level, but he especially loved children. My earliest memory of Zaidy is him playing with my fingers, trying to find the one that he claimed had “disappeared”. “Hmmm, this is interesting”, he exclaimed, “You only have 9 fingers!” His talking watch was another source of endless fascination to us children.

As a grandfather, Zaidy was very loving. He would feel our faces and tell us that he has beautiful grandchildren. Although he never saw our faces, it was uncanny how he could follow our thoughts.

My siblings and I spent several Shabbosim with Zaidy in Aunt Nina’s house. Zaidy was fun to spend Shabbos with because he so enjoyed participating in everything. We would sing Zmiros with him. Everything he did was done in a complete way. When he sang with us, it was with his entire heart and soul. Although he did not have a melodious voice, he more than made up for it with his enthusiasm and joyous smile. Even when he didn’t have the strength to sing, he would bang on the table.

Zaidy always encouraged our learning. To him, it was like breathing. We knew to be prepared for a grilling about anything we mentioned learning in school. In both secular and religious topics, Zaidy could test us and teach us something we hadn’t known. In Jewish studies, we knew that with a prompt of only a few words, he could — and would — recite most things from memory, and that included the Bible, the Talmud, and commentaries.

Zaidy respected every point of view, as long as it was logically consistent. I remember an incident that occurred while I was reading to him a book he had authored. He suddenly stopped me and asked what my opinion was on what he wrote. Knowing the high value he placed on intellectual honesty, I answered “I think it borders on the heretical.” He very much enjoyed that.

He was an extremely honest person with strong principles. He believed that knowledge cannot be hidden and should be in the public domain. Although he possessed a very easygoing personality, he did not hesitate to stand up for his principles, as in the matter of publishing the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Zaidy was a Holocaust survivor. With his talent for languages, he was able to pass himself off as a gentile laborer. Although we asked, he did not share much about those frightening times with his young grandchildren. Instead, he told us the humorous story of how he passed time teaching “Gemoorah” to the cows while working in a farm. “Ge-MOOOOO-rah”, he emphasized, with that special twinkle.

Education was so important to him. He came to America in his late teens, and earned a doctorate degree. When I was in high school, he would always ask me, “Are you in college yet?” When I reached that point, he was no longer able to converse in depth about each course, but he immediately wanted to know what I was going to study for a doctorate degree. He was so happy whenever he heard that someone was pursuing higher education. To Zaidy, learning was everything in life.

Although he lacked sight, he possessed the sharpest insight. He sensed when someone was not being completely honest with him. Zaidy only wanted to hear the truth. Maimonides says, “Accept the truth from wherever it comes” and Zaidy excelled in this. Consequently, he loved critiques of his work and sought them out.

Zaidy was a proud Jew and a true “Person of the Book.” He authored many books and articles during his life and wanted the last book he published to be an autobiography.

Every visit involved a lot of reading. He never tired of it — instead, the more he learned, the more he wanted to learn. More recently, we would read him the last book he published, The New Damascus Documents: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Reconstruction, Translation, and Commentary. He was very proud of this book. He most loved hearing our questions about his work. Whether explaining “eschatological” to a 12 year old or debating a Talmudic point, Zaidy would go to great lengths to make sure he was understood.

For as long as he physically could, Zaidy insisted on going to shul to pray. This involved a long and tiring walk, but he loved the atmosphere in the synagogue.

Zaidy loved all of his grandchildren deeply. He expressed this love through loving words and actions, but most importantly by instilling a love of learning and thinking. Each grandchild perceived Zaidy in a different way. Zaidy was like that. He spoke many languages and was a polymath. No one could compete with him in depth or breadth of knowledge, so he would discuss whatever interested us. In this way, he made us feel comfortable with him and was able to teach us as only he could. I know I have only merited to glimpse a few aspects of the complex person who was my grandfather.

It would make him happy to know his children are going to Israel together with him, and that his grandchildren remember his example and his accomplishments, and value his legacy. And yes, Zaidy, we are going to read your book.

(2) Sholom Wacholder’s talk at Ben Zion Wacholder’s Memorial Service in New York

As I sat on the train this morning preparing, and debating whether I should speak with the help of a computer, I looked to my father’s example for answers. And I decided, Whenever you have something to say, the key is to express yourself well within your capabilities: don’t worry about convention and don’t worry about everything you do not know when the goal is to achieve an important end.

In recent years I have heard many mourners tell stories about a beloved person who has died. But funny stories or camping trips or sports events did not come to mind as I remember my father these past few days. Instead, I want to share one dominant aspect of his person and of his personality.

My father knew all 613 mizvot, but he profoundly personified one of them. He would have been happy to observe the mitzva “v’shinantam l’vanecha” – Teach them [teach God’s words] to your sons— every waking hour of every day.

He had expansive views of these words. To him, God’s words encompassed all the texts he studied so joyfullly: the Torah, and the Talmud, and the Midrash, and the Rishonim, and the Acharonim, and contemporary she’elot and Responsa and academic Judaica scholarship too. And God’s word encompasses science and history and philosophy and math.

To Daddy, “Teach these words to your sons” has an expansive definition of “sons.” Not just David and me, but Nina and Hannah, and 15 grandchildren, and in-laws too. His sons included every student he had in a class, or anyone who would listen to him and respond. Young or old. Male or female. Jew or non-Jew. Just ask the aides who took care of him for these past few years.

To my father, teaching encompassed learning. He learned so he could teach. He taught so he could learn more and teach better. His life was not balanced. He was obsessed. His obsession was not food, or art, or music, or movies or sports. His obsession was “torah lishma.” Torah for its own sake. He always wanted to understand my work, about as distant from the focus of his own study as possible, and see whether it would help him learn and teach. And he created disciples who follow his example: As I made phone calls yesterday, I heard at least twice, once from a rabbi, once from a Christian scholar: “Ben Zion changed my life.” He changed many lives: not just those he knew intimately, my mother, my sisters and brothers, but everyone he knew. That is what teaching by doing accomplishes.

Over the past years of slow cognitive decline, my father developed a tic. Almost at random, he would ask “Have you read my book?” Many times a day. Sometimes once a minute. I see this tic as an expression of his frustration at not being able to learn and teach at a high level. He was begging for us to engage with him in his work to force him to learn more deeply so he could teach more fully and more effectively. He was really saying: “I want to hear your thoughts about my work: Your questions, your challenges to my interpretation. I want you to teach me something new so I can learn more and teach something new about the Damascus Document.”

My father’s example of living the holiness of Torah lishma is his most profound teaching. When our own lives transmit his love of Torah, lilmod u’lelamed, to our own children, our students, our mentorees, our friends and acquaintances, we are simultaneously honoring Daddy’s memory and fulfilling the mitzva of “Ve’shinantam levanecha.” And as those who learn from us teach or grandchildren and grandmentorees, we preserve and perpetuate an ancient tradition in infinite progression, and honor ancestors who created the tradition; direct ancestors, and ancestors who are unrelated to us genetically; ancestors whose names we remember and ancestors whose names we do not know.

(3) Hannah Katsman’s eulogy for her father Ben Zion Wacholder

Once, when I was about ten, I repeated to my father something I had heard or read somewhere: That the only two English words in the English language with no rhyme are “orange” and “silver.” A couple of hours later, when he happened to pass me in the hall, he said only one word. “Chilver.” “Chilver’s not a word,” I challenged him. “Look it up,” he said. At that stage in his life, he couldn’t see well enough to read. So I went up to his study, where he kept an unabridged dictionary open on top of the file cabinet. Sure enough, chilver was listed. For the record, it means a female lamb.

This was typical of my father’s approach. He never took anything for granted. When he heard a statement of fact, he immediately questioned it. He enjoyed the intellectual challenge of examining facts and looking at a question from various angles. Maybe there is something that rhymes with silver. He didn’t argue to demean others or to prove he was right. He just wanted to find out the truth.

Several years later I mentioned the incident to my father, how I was impressed that he knew the word chilver. He admitted that he hadn’t actually known whether or not chilver was a word. He was making a guess, which he wanted me to confirm as true or false.

John Kampen and John C. Reeves, students who edited the festschrift in honor of my father’s 70th birthday, wrote: “All of us remember occasions when the results of his most recent research contradicted his own earlier conclusions. “So I was wrong!” was a frequent response to queries about his own earlier judgments.”

When my father’s theories were attacked by colleagues in the academic world, he never took it personally. In fact, he relished the attacks because they gave him a chance to return to the texts and find something he might have missed. He loved to learn things that shed light on a question. It didn’t matter whether or not the information ultimately supported his position.

For his children, students and colleagues he was a model of authentic scholarship. As a child I was amazed by his complete dedication to his work, often until the early hours of the morning. You would find him in his armchair near his typewriter. Occasionally he would be reading with the help of a magnifying machine—he needed the highest level of magnification, which allowed him to read only one or two words at a time. My bedroom was on the same floor as his study, and I can still hear the ping that signaled the end of the line on the manual typewriter. When you reread his work, though, many of the lines still went off the page. Typing without sight, he spelled out his thoughts that he later reviewed with his students. With the advent of new technology, he progressed from a manual typewriter to an electric one, then an electronic one, and finally to one of the earliest computers that read text aloud. Of course, few of the basic Jewish texts were digitalized at the time, much less the obscure ones he specialized in.

But mostly he sat in his study for long hours, just thinking.

Whenever I stopped by the study, whether to call him to dinner or relay a message from my mother who rarely climbed the stairs, he invariably asked me to look up a few of the sources he was working on. He would say, “Take out Josephus,” or the Book of Jubilees, or Encyclopedia Judaica, or the Gemara. The walls of his study were lined with books—my mother refused to allow bookcases in the living room—with many more piled on the floor. My father would direct me to the correct shelf and help me locate the page—he knew every one of his books intimately.

During high school my father summoned me to spend hours in his study, mostly reading Yigeal Yadin’s new commentary on the Temple Scroll of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which fascinated him. In recent years, he would be happy with an offer to read any text, although he preferred to hear his own newly published book on the Damascus Document. One when I was reading it to him, he remarked, “You read very well.” I had a lot of practice.

Officially his field was Talmud and Rabbinics, and he taught the Talmud, Shulhan Aruch and other texts to Reform rabbinic students. My father enjoyed teaching beginners as well as the series of advanced doctoral students who spent several days a week at our house, studying with him both in their own fields and whatever my father was researching at the time. My mother served them lunch and they became part of the family. A couple of years ago one came to visit me here in Israel while leading a Christian group from the Philippines.

When I told one of my friends about my father’s death, she pointed out that my father lived the life he wanted to live. He got paid to teach, write, and mainly to think about the things that interested him.

It wasn’t always easy being the daughter of a welll-known Jewish scholar. Once, a friend talked me into accompanying her to ask our public school teacher to give us an extra few days to study for a test, claiming that we needed the extra time because we had to prepare for the upcoming Passover holiday. The teacher, who wasn’t Jewish, looked at me closely. “Hannah,” she said, “Does your father know about this? The teacher was right, of course, as my father didn’t know and wouldn’t have approved.

My father was also well-known around the neighborhood for his long daily jogs in all weather. Occasionally he got lost or injured, and a stranger, or sometimes a policeman, would bring him home. My mother once insisted that he tell her his usual route so we could locate him if he failed to return. When his picture appeared in the paper because of his work on the Dead Sea Scrolls, we learned about the many friends of all ages he had acquired on his walks. They saw him as a blind, eccentric and very friendly fellow, and were shocked to learn of his international reputation.

I visited him every summer in recent years, taking along a few of my children for him to enjoy. It was sad to see him decline, yet we also saw a flowering of affection toward his children and grandchildren.

[At this point Hannah read the eulogy written by Tzipora Wacholder.]

Students, Colleagues, Neighbors, and Friends

(1) Thoughts from Rabbi Ned Soltz – Teaneck, NJ

Dr. Wacholder touched and inspired so many of us as our beloved teacher of Talmud and mentor. I last saw him in Cincinnati at Rabbi David Ellenson’s installation and told him in all sincerity that not a day passes when I do not think of him and insights into the Bavli and Yerushalmi he shared. My deepest condolences to the entire family. You have lost a beloved father and grandfather. We all have lost a beloved teacher and friend. Yhi Zichrono Baruch.

Source: Legacy.com Guestbook

(2) David Maas, Ph. D. (Assistant Professor of Old Testament/Instructional Mentor Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary) remembers Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l

While the biblical David slew a giant, this David has stood on giant’s shoulders. There are a few giant figures that come into one’s life. Dr. Wacholder was one of those giants for me. I have only good memories from our time together. Your dad was always very kind to me, and patiently endured my sometimes feeble efforts to read the primary texts in the many linguistic universes he inhabited.

His prodigious mastery of these texts are well known, and separated him from his peers. I think that a scholar of his magnitude only comes around once in a lifetime. He will be remembered for generations to come in the world of academia. Yet, what stood out to me the most was his willingness to challenge the scholarly community. He taught me to continually examine even fundamental assumptions by which scholars live by. This is a legacy this giant has left with me.

I will remember your dad always,

David Maas

Dear Nina, Hanna, Shalom, & David:

I do wish I could stop in this evening, sit with you, and honor your father. Instead I have set aside my own evening here in BC to gather the thoughts that have been swirling through my mind since Shalom called me with the news of Ben’s passing this past Tuesday.

I arrived at HUC in the summer of 1987 after spending three years studying in the department of Comparative Semitic Languages at the Hebrew University. In my final year at the HU I had taken a course with Emanuel Tov, “Issues in the Judean Desert Manuscripts.” This course proved to be one of the defining moments of my academic life. And it was in midst of this seminar that I first heard the name of Ben Zion Wacholder: in the context of the Temple Scroll and his study, The Dawn of Qumran. When it came to the choice of Ph.D. programs in North America I finally settled on HUC, partly because the College offered the best financial support, but largely because of the reputation of Ben Zion Wacholder.

I remember well my first conversation with Dr. Wacholder, sitting along the wall on the second floor of the “Classroom Building” between lecture sessions. I had heard he was looking for a graduate assistant and I proposed myself. In ten minutes he had sized me up and signed me up. Little did I know at the time that this research assistantship would eventually morph from a 10 hour a week job into the adventure of a lifetime.

I could wish I had kept a journal. As I have said elsewhere, I think that in the hands of a gifted storyteller the tale of the next 7 years would rival Mitch Albom’s, Tuesdays with Morrie. Mine was “Tuesdays and Thursdays with Ben Zion.” And, oh my, I learned so much more than the contents of Jewish literature. Two prime examples: he taught me that it never hurts to ask; the worst that can happen is that the answer will be “no.” In a taxi on the way from the hotel to a conference session at the University of Haifa, Dr. Wacholder found himself in the company of Harvard professor, John Strugnell, editor and chief of the Dead Sea Scrolls publications. Dr. Wacholder asked about the existence of a rumored secret concordance to the Dead Sea Scrolls. Upon verification (which Strugnell had denied elsewhere, but you just don’t lie to a white haired blind man!), he then asked that the HUC library might be provided a set. I have kept a copy of the letter from Strugnell granting HUC permission, to remind me that simply “asking” quite often pays off.

From Dr. Wacholder I learned never to turn down a request for help. On a trip to New York City for a press conference in the fall of 1991 we took a walk together around Central Park (Ben was a great walker!). He made sure that he had a thick wad of bills in his wallet. As we toured the park he handed them out, one by one, to anyone who asked. No debate about what the recipient was going to use the money for, or comments about how they should find gainful employ; if someone asked for a handout, it was clear they needed help. My wife Sue and I remind ourselves of this regularly and refer to Ben’s example when we are tempted to hold back.

And then, of course, there are the textual tales. Concerning boldness: on March 15, 1988, in my normal course of duties I picked up Dr. Wacholder’s mail at HUC and took it out to the house on Greenland Place. Among the letters and journals was a brown manila envelope with no return address. Upon opening it we discovered a 20 page photocopy of a handwritten Hebrew text. I didn’t read him more than two lines before Dr. Wacholder announced, “This is Milik’s unpublished 4QMishnaic.” As indeed it was; now known more commonly as 4QMMT, or Miqtsat Ma’aseh Hatorah. Using the 20 page photocopy as a textbook, Hell Lit 25 (4QMMT), was listed among the courses at HUC in the spring of 1989, certainly one of the most unique and daring course offerings in the history of graduate studies. After all, the brown manila envelope could have contained nothing more than a cruel joke. Thankfully, when the official volume appeared 7 years later, it became clear that the photocopies represented a rough draft of the editor’s transcription. Those of us in Hell Lit 25 were given a significant head start on rest of the scholarly world. I myself have published 4 articles directly related to conversations that began in the seminar room across from Dr. Wacholder’s office on the second floor of the Klau.

Concerning justice: the Preliminary Concordance, that the Haifa taxi conversation eventually produced for the reserve book ‘cage’ at the Klau, provided—with a bit of reverse engineering—a number of texts I needed for my dissertation. In the midst of this work, I noticed the unpublished manuscripts of the Cave 4 copies of the Damascus Document. I reconstructed them with the thought they would come in handy for the study that Dr. Wacholder had begun (that eventually produced, The New Damascus Document, his final scholarly publication in 2006). When I plopped down the 80 page printout on his desk in the spring of 1991 his first words were, “This must be published!” When our book appeared in September, a 40 year embargo to the access of the Dead Sea Scrolls became a curiosity of history in two short months. There are very few today who would not agree that Ben Zion Wacholder’s decision to publish was just. An entire and unique generation of Jewish scholars had been denied the privilege of studying what amounted to an important new chapter in the history of ancient Israel and Ben was not about to see such an injustice continue.

Of course, the pay off for me was that Ben and I spent the next four years reading through the entire corpus of the Dead Sea Scrolls in order to prepare the three fascicles of our “unauthorized edition.” And a perusal of the 32 “authorized” editions that have followed (the final publication just last month) reveal the name Wacholder-Abegg liberally scattered throughout, as the editors demonstrate they were quite pleased to have access to the original transcriptions that our efforts had provided them. For me the reference “Wacholder-Abegg” transports me back to Ben’s study in Cincinnati, pouring over texts, debating reconstructions, and learning from scholars who had been involved in a similar enterprise, 2000 years earlier. Long to short: my experience with Ben was that which every graduate student dreams about but few experience. What a blessing. I will greatly miss Ben Zion Wacholder, my mentor, my doktorvater, my friend, and my partner in crime. May his memory be a blessing.

(4) Memories from Timothy Clontz

Ben Zion Wacholder was the man who broke the monopoly on the scrolls by brainstorming the reverse engineering of the concordances. The resultant text was over 97% accurate, and led to the full release of the texts to the world after decades of gridlock. For scholars of any religion, he was a hero. And for those of us who met him — he was a most unassuming and kind hero. He will be missed.

(5) Memories from Rabbi Charles Arian (Norwich, CT), originally posted on Facebook

Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, emeritus Talmud professor at HUC, passed away yesterday. He made many important contributions to scholarship and played a key, and controversial, role in finally making the texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls available to the general public and to scholars not part of the little group which then controlled them.

He was a Holocaust survivor and had studied in the great Yeshivot of Eastern Europe before the war. He knew all of rabbinic literature by heart and subsequently developed an expertise in the Greek and Latin classics as well.

When I was a student at HUC, it was well before the Internet era. In my senior year I took an advanced, Hebrew-language seminar in intellectual history and we were reading the ethical will of the Hatam Sofer. We came across a term that no one in the class knew, including the professor — a world-class historian in his own right. I announced to the class that though I did not know the meaning of the term, I guaranteed I would find out and report back to the class at the next session.

The next week I indeed came back with the correct translation. “How did you find out?”,” the professor asked. “I asked Dr. Wacholder,” I replied. “I knew that he would know.” Ben Zion Wacholder was my Google before Google was invented. I regret not having seen him very often in the years since graduation. He was a great man.

(6) “In memory of my teacher and mentor, Ben Zion Wacholder,” from Rabbi Gil Nativ, Congregation Magen Avraham

I was fortunate to study Talmud with my Ph.D mentor, Prof. Ben Zion Wacholder, for almost five years: From the end of 1985 through the summer of 1990. Since I was the only Ph.D candidate majoring in Talmud at H.U.C. during these years, this was a one student course he taught, and most of our study sessions took place at his home in Roselawn.

By the mid eighties, Prof. Wacholder was almost blind. I would sit in front of him and read aloud, and whenever I missed a word, a phrase or a line, he would stop me and say the missing word or phrase —“ sometimes it was attributed to his excellent memory of Talmudic texts he had studied as a young yeshiva student, and sometimes he simply noticed that what I had read did not make sense, and figured out what was missing. I will attempt to condense in two sentences two seemingly trivial things about the Talmud which I learnt from Prof. B.Z.Wacholder:

1. The Talmud is One — One may argue whether the redaction of the Talmud was done mainly by the last generation of Amoraim or by the later Savoraim, which group had more influence, how much liberty the redactor took with the orally transmitted texts etc. but one cannot claim that certain tractates or chapters are the product of different sages with different concepts or methods: There is one underlying method and the same concepts and terminology permeate this entire monumental work.

2. The Talmud is a Masterpiece — A literary masterpiece is defined by having several levels of understanding and meaning: One can study the Talmud by deciphering the text (with or without Rashi’s commentary) and another can probe deeper into layers of concepts, logics and views. For 15 centuries scholars have explored and found deeper layers of conceptual, philosophical and life-guiding messages in the Talmud.

When the news that B.Z.Wacholder passed away reached me, I was at the annual convention of the Rabbinical Assembly. On the following morning I said the following “Dvar Torah”:

A well known mishnah (Sanhedrin 10:1) teaches: “Kol Israel yesh lahem heleq la’Olam haBa”: (The prooftext is Isaiah 60:21). The common understanding of this mishnah is that the soul of each of us, after completing life in this world, will merit eternal life in “Olam haBa,” the hereafter.

Ben Zion Wacholder was convinced that this is NOT the original intent of this mishnah: He explained that the phrase from Isaiah “leOlam yirsho aretz” refers specifically to Eretz Israel, and that Tannaim believed that after the end of history, and as a result of “Techiyat haMetim” every Jew will have a share, i.e. will own a plot, no matter what size, in Eretz Israel.

BZW wanted to spend his retirement years in Eretz Israel, and was already looking for a place to live there over a decade ago, but for health and family reasons, remained at the home of his daughter, Nina, in Long Island. His body is being brought today to Eretz Israel, to have a share, a “heleq,” in the promised land.

(7)Shabbat Pesach, a story from Rabbi David Wilfond

On the last day of Pesach, Yizkor (memorial) prayers are said. It is during holidays that we often feel more keenly the loss of our loved ones. A few days ago we sat at the Seder. We remembered the happiness we shared for many years sitting with family singing songs, drinking four cups of wine and talking about Passover’s message of freedom. Now the empty space at the Seder table reflects the empty space we feel in our hearts.

A few weeks ago one of my Rabbis passed away, Rabbi Ben Zion Wacholder. He was the teacher who most inspired me during Rabbinical School studies at Hebrew Union College. I would like to dedicate this “Shalom LJS” article in memory of my recently deceased mentor and beloved teacher. The following story happened a few years ago.

The telephone rings and the caller says “Rabbi Wilfond would you come and lead the Seder in Baranovich.” Baranovich, the caller tells me is today in Belarus but was part of Poland before The War. I think to myself…hmmm… I know this name. I think this is where one of my Rabbis from Rabbinical School went to Yeshiva before The War’. I telephone my teacher Rabbi Wacholder and tell him that I am going to Baranovich. He says —œyou must take pictures.— “Huh?” I replied thinking about Rabbi Wacholder being blind for over 20 years and stammer “Why do you want photographs?” “It is not for me,” he says “it is to show my grandchildren. And find the Yeshiva, there was only one in Baranovich.—”

A few weeks later I arrive at Baranovich in the morning by train from Minsk. Seder will be at night. We have a few hours. I ask “is there a Yeshiva here?” “Yes, the old building survived The War. Do you want to see it?” We walk over. It’s a big old building in what was once the Jewish neighbourhood. It is now a sports college. Behind the building there’s a running track with men stretching and running. I think how ironic. A Yeshiva — a centre for spiritual learning has become a place of physical education. This is symbolic of the Soviet inversion of Jewish culture — the spiritual reduced to the material. Around us are wide streets with small wooden homes and trees. My host tells me these are Jewish homes from before the war. “This is the old neighbourhood. 12,000 Jews were killed here when it was turned into a ghetto, but most of the buildings survived.”

That night we lead the Seder in a large room where about 100 people crowded in. I see an Aaron HaKodesh with a Torah and ask, “Does anyone read from the Torah?” They say “No. It was gift, but we don’t know how to use it.” Well, there is one part of the Haggadah that is actually a long quote from the Torah, so I decided to do something a bit unorthodox. In the middle of the Seder we took out the Torah, did a hakafah (a procession) through the congregation and holding up the Torah scroll so all could see, I read in Hebrew and translated into Russian “and with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, I the Lord Your G-d Brought you forth from the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage so that you might dwell in freedom in the land of your ancestors, a land of milk and honey, the land of Yisrael.” When the Seder was over I said “I must tell you something important and personal. I explained many things about Passover and the Haggadah tonight. But the things I taught you — I did not make up. Most of this I learned from my Rabbi in Rabbinical School; Dr. Wacholder, who studied here in the Yeshiva of Baranovich before the war. Somehow he survived, got to America where he taught a generation of Rabbinical students — I was one of them. So tonight I am returning to you the teachings of Torah that used to come from this town. Please don’t forget what you heard and learned tonight. Tell it to your children your friends; repeat it next year at Pesach so that the Torah of Baranovich is not lost.”

There are a few times in life when we get a feeling that perhaps it is for this I was created. Perhaps to do this one act, perhaps for me carrying back Rabbi Wacholder’s Torah to Baranovich was the fulfilment of something greater. This year when we say the Yizkor prayers at the end of Pesach, I will be thinking of my beloved teacher and Rabbi Dr. Wacholder. I invite you to come to Yizkor to remember, to pray and to reflect on the blessing of the lives that have touched our lives.

(8) Hesped for Rabbi Wacholder, from Rabbi Ed Boraz, Rabbi of the Dartmouth College Hillel

The phrase “ukneh lechah rav” resonates in my soul. Rabbi Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l, gave me such a great gift in being his talmid and he being my Rav. The loss is as profound for me at this moment as anyone in my life, including my own father, who has passed away.

He embodied the dream of klal yisrael. He was observant; no question about it. He davened every day, would go to an Orthodox Shul down the street, but sometimes would come to my little shul on Shabbat and daven there, without a mechitzah (he was not a conservative Jew, he was klal yisrael). Always, I would ask him to give a d’var because his wisdom and his gentleness with which he approached the text, was so good and pure.

He studied as a child in the great Lithuanian Yeshivas where they recognized him early on as an Ilui (a child prodigy of the Talmud), survived the Shoah though no one in his family did, and received his smichah from Yeshiva University in 1952 (?). He then somehow earned his Ph.D. from UCLA. He taught at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati for a long time. When I earned my Ph.D. from him, I knew that was my real smichah. He had asked me to stay on as a graduate student and I remember going to Larry Moses and Rabbi Corson of the Wexner Foundation and asking what they thought I should do; both of them resolutely told me to stay and to study. I did and I am a far better Rabbi for having done so.

My little book – Understanding the Talmud: A Modern Reader’s Guide for Study – was my rabbinic thesis (not dissertation). It was his methodology, so he is the author in the truest sense of the word, so I can only take very little credit for it.

He was completely blind when I studied with him and yet he knew the entire Torah by heart; his memory and mind were so sharp, and his heart ever so kind.

His greatest impact on me lies in two things. One was when I began studying with him at his kitchen table one summer in the 3rd year of my rabbinical school training. Each day in the morning I would go to his house, he was living alone at the time, and we would and learn. I would read Gemara and he would just explain things so beautifully and so sensitively. The atmosphere is what I remember more than the substance of his teaching. The other was the walks we would take. He loved to walk at least four to five miles every day, and he would sometimes walk alone, and sometimes even at night, which was frightening. But when I would accompany him, which was often, in those walks, he taught me so much because by that time, I had a small congregation and took many problems that I was having, and just life in general, and would seek his guidance. His gentleness, his wisdom, his approach – he was the Rabbi that I long to be, and yet I feel I have fallen so short. He understood so much about the essence of wisdom of our faith.

Sometimes there are simply no words, the words that do come to mind are so overused, and not unique, such that they sound like a cliché even when they are not intended at all to be. There are just no words now. There is emptiness in my heart that becomes soothed when I think of him.

He would come each day to services at HUC at 11:00 a.m., which, even for someone as liberal as me – were a little strange – circle sitting, stuff like that – profound changes in the liturgy – lots of experimentation – and there he would be….. never having a bad word to say, never critiquing a particular sermon (except to me privately and I knew he had one standard – was the Rashi cited – any Midrash – was the sacred text being brought forward – if not he might privately be critical – saying in that thick Yiddish accent of his – “Nu…. it was a little….. thin” (by saying so little he could say so much). But he was always there for his students.

Once, someone asked him (can you imagine losing everything in the Shoah – your entire life and then being asked the following), “Did he believe that God gave the Torah to Moses at Mt. Sinai as it is described?’ He responded (in his thick yiddish accent), “Well, I don’t know. I wasn’t there, but the people who were there, said it did. Nu, let’s read.” Then he would call on someone.”

Belief was not as important to him as was learning. I once asked him, “Rabbi Wacholder (he always wanted me to call him Ben Zion but I never did – I couldn’t), you were in some of the finest Yeshivas in the world and there students would know so much compared to our barely scratching the surface. Is it difficult to teach here in light of the discrepancy?” His response was so beautiful. He said that here there was much more questioning of the text. Students here bring a fresh understanding, inquisitiveness because of their backgrounds than what was there. True, they don’t have the background and not everyone will fall in love with the text (that is how he always referred to the entire body of sacred literature (Tanakh, Midrash, Talmud, Codes), but that some would and that for him was so satisfying;

You may hear a lot about his work on the Dead Sea Scrolls, but I know with absolute certainty that it was only a hobby for him; a kind of indulgence. His love was always “The Text.” His legacy to me is that “The Text is always the kedushah.”

(9)Remembering Dr. Wacholder, from Rabbi Stephen J. Einstein

I first met Dr. Wacholder when he was serving as Librarian at the California School. Years later, I would see him on the Cincinnati campus. Though I never had the joy of studying with him, my fellow students spoke of him with admiration.

The evening before ordination in 1971, Dr. Wacholder spoke at our consecration service. He raised this question: Who will bless the rabbis?

He noted that rabbis are often called upon to bless people–at a bris or baby naming, a consecration, a Bar or Bar Mitzvah, a Confirmation, a wedding. He then asked: Since rabbis are always blessing others, Who will bless the rabbis?

His answer has been the hallmark of my rabbinate for four decades. He proclaimed, The People will.

Above my desk, I have a needlepoint with Rabbi Wacholder’s question and answer. It is a beacon to me every day.

The memory of this great scholar will remain a blessing.

(10) A Memory from Akiva Wagschal

I have fond memories from the early eighties of walking Reb Ben Zion home from Knesseth Israel on Shabbos morning. It was delightful to be in the presence of an “alter Litvishe yeshiva man”. Though I wish I had some pearls of wisdom to share with you that I recall from those walks, I’m sorry but I don’t remember them. But I do recall the general feeling that I was walking with a huge talmid chochom and what a privilege it was for me to be close to and hear his opinions on the vertalech we would sometimes share on the parsha.

Back then I was trying to sit for a licensure test to be a Nursing Home Administrator but The Board denied me that opportunity because I didn’t have a baccalaureate degree from a conventional American University. All I had was the transcript from the five years I had learned in Gateshead yeshiva. A member of the board of examiners by the name of Mort Wiesberg from Cleveland, suggested that I get my transcript certified by the Telshe yeshiva in Cleveland and I pointed out that the board doesn’t recognize Telshe as an American Association of Advanced Rabbinical Training Schools approved college. So he said, but I see you live in Cincinnati, I am sure we recognize HUC. I pointed to the yarmulke I was wearing and I said, do you think a Reform Rabbi school would accept the transcript of an orthodox yeshiva? He smiled and said, why don’t you ask them?

So the next shabbos while walking home from shul with Reb Ben Zion, I said, “nicht shabbos geredet, but this is my problem, do you think the admissions office would do that for me? He said, bring it to me after shabbos and I’ll show it to Dr Sam Greengus. And that is how a Gateshead yeshiva bochur got his chinuch in Gateshead approved by HUC 🙂

I think I recall him suggesting that the Essene sect to whom the dead sea scroll are attributed to, may have been the Chassidim that we learn about in the Gemoro when it talks about the Chassidim Harishonim. Now I could be totally wrong about that, I may have suggested it and he may have debunked it. But I do remember him in his study at home with the huge magnifying contraption and discussing whether there were any ‘chiddushim we can derive from the scrolls,’ He said their chumros in Tumoah and Tahara were never accepted by the hamon am.

He was a very dear man and I am glad to see that he left behind children and grandchildren who carry on the mesorah.

Yehi zichro boruch.

back to top

(11) Memories from Madeleine Isenberg, a Student ca. 1954

I’m sorry, but I’ve looked everywhere and I can’t find it. It’s an old letter I wrote to a former teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Ben Zion Wacholder.

In my mind, I see him as I did then, in 1954 — a scrawny young man wearing a black suit and fedora hat, thick black horn-rimmed glasses with coke-bottle lenses. His tobacco stained fingers shook as he chain-smoked while attempting to teach our class. But we pre-adolescents were merciless. We talked in class, passed notes to one another, and taunted him.

Little did we know then, that he was a Holocaust survivor from Ozarow, a shtetl in Poland. At age 18, in 1942 he had fled and had lost his entire family — his parents and three siblings. For about five years, he managed to survive pretending to be Polish and working on a farm. In 1947, he eventually found his way to Williamsburg, NY. He obtained his BA and ordination in 1951, from Yeshiva University. So by 1954 in Los Angeles, he was encountering us somewhat early in his pedagogical career. I think he only lasted a year or two at the most, perhaps leaving in frustration because while he had so much Talmudic information to impart, our unruly, misbehaving class, was not amenable to paying attention to this pathetic-looking person.

In 1956, he became librarian for the Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion, and joined its faculty a few years later. In 1960, he also earned his doctorate at UCLA.

I did not see him for years, but I think it was in the 1980s, that I would occasionally see him at one of our local synagogues (Beth Jacob). I’d smile and greet him, and he would smile and nod back in recognition. But I always felt a gnawing sense of guilt for my participation in his humiliation during those early school years.

Then in the early 1990s, his name popped up in a Time Magazine article about the Dead Sea Scrolls. It seems he became quite a scholar and published many books. He and his assistant, Martin Albegg, published a “computer-reconstructed transcription of scrolls based on John Strugnell’s unpublished concordance.”

Reading about this piqued my interest on at least three accounts: My recollections of by then, Professor Wacholder; my interest in old Hebrew documents; and my profession as a computer programmer. Since the article indicated that he was now at HUC in Cincinnati, I knew how to contact him. So I decided it was high time I wrote a letter of apology.

I wrote it very respectfully and indicated my reasons for being interested in his work, and then apologized for the past behavior of the entire class, almost 40 years earlier. While I really couldn’t speak for everyone, wherever they were then living, I felt that someone had to do this. The hardest words to utter are, “I’m sorry” and I felt relieved about finally getting my guilt off my chest. I hoped I would hear back from him. But I didn’t.

I’ve often wondered if our mistreatment of him wasn’t really a blessing in disguise. Having given up as a teacher of young bratty kids, he went on to pursue bigger and better things, and to teach at a level at which he was better appreciated. I’m not sorry about that.

(12) Obituary by James Bowley Delivered to the HUC Board of Governors

Ben Zion Wacholder was my teacher, mentor, boss, friend, co-author, and seemingly a second father to me when I was a student at the School of Graduate Studies from 1986 to 1992 and long after. He embodied so many characteristics of the best of our tradition, and for us as Governors, he exemplified so many of the best things of this Institution that we are privileged to serve; he is today, a blessing to me and to dozens, even hundreds of other students and people who knew him well. No matter how entertaining the business meeting David has planned for us today (ha!), it would be much more enjoyable to listen all day long to stories about Dr. Wacholder, but I will only speak briefly as to why. He was odd, loveable, feisty, kind, sharp, funny, and so much else.

If he were here today listening to me, he would be sitting in the front row, as he often did at professional meetings, and by now he would have already asked a question, and a follow-up question. He was insatiably curious, and would ask and learn from, and teach anyone. He was no respecter of persons, and, just as he survived in life, he was fiercely independent as a scholar and teacher and thinker, and today when I study, I think of him and wonder, how would he disagree with what I, or anyone else has written or said? And disagree and question and ask, he would, constantly. He would not be pinned down or categorized intellectually, ideologically, and was no partisan for a party or denomination. He was a recognized young scholar in the yeshivas of E. Europe, he was ordained at Yeshiva University and then earned a Ph.D. in Classics at UCLA, and, he was for all of his teaching life a wonderful presence at HUC, Cincinnati.

According to Pirkei Avot, the Men of the Great Assembly said: “Raise up many disciples”

Ben Zion was employed by HUC for more than 50 years, oversaw 20-some Ph.D. dissertations, and dozens of Rabbinic theses. Among his students and colleagues, his learning is legendary and inspiring. Ask any rabbinic student who had him, and they’ll probably mention the pin-through-the-Talmud-page story, in which Ben Zion’s memory could tell you exactly what words were written at any exact location on any given page of Talmud, if you told him the words on the other side of that page at that location. For me, sitting in his study at his house, one or two days a week, reading and debating, he would recall Talmud, Bible, Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars’ articles, and just start quoting seemingly everything. One day when we were taking a break and sitting at his kitchen table, I mentioned that I was reading Don Quixote, and he proceeded to quote the first paragraph from memory, in Spanish, which he learned in his days in Columbia, where he fled after the war.

Today there are teachers and rabbis all over the world, North America, Israel, Europe, South America who still stand on his shoulders and remember.

But he was so much more than intellectual. Ben Zion was generous to a fault. Always welcoming students and families to his sukkah, giving Christmas and Hanukkah presents to his student workers, and taking me and others to lunch at least weekly when I worked at his house, to the deli in Roselawn or Marx Hot Bagels behind his house. Every year at the meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Ben Zion would treat all of his graduate students to a meal, taking us all out to a nice restaurant. This generosity was born at least in part from his memory, his past, his tragic family story. The author of Deuteronomy writes: “You must love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

Ben Zion was a stranger—and so much worse—in the land of Poland, and though he talked little about it, he never forgot. When we would walk with him in cities he would always, always, give money to any homeless person or beggar that he saw; and he would search them out. I picked up his mail at school and at home sometimes, and it was clear that he was generous to many causes that aided the oppressed. Most of his books, from the first in the 1962 to the last in 2006, are dedicated to persons in his immediate family, his father Pinhas Shelomoh, his mother Feiga, his sister Sarah, his brother Aharon, and his sister Shifra, all of whom perished. He was the lone survivor of his entire family. The words of Job ring true: “And I alone have escaped to tell you.” And tell us he did. He told us and taught us and created knowledge of Talmud, Bible, history, Dead Sea Scrolls, and life. Read any history of the Dead Sea Scrolls and he will figure prominently, appearing on the front page of the New York Times in 1991 because of his fearless independence and courage.

Forever, he will be my beloved teacher and friend. He lives on in me and in so many others, as teacher and as human. Daily he inspires me and makes me question and smile. He is a vivid memory, an energetic and lively force in the world, and always a little bit ornery, a living power in my world, our world, the world of Jews and beyond, today.

I am proud to be on this Board of Governors of the Hebrew Union College, if only for the reason that this Institution supported and nurtured and made possible the long scholarly career of our beloved teacher, Ben Zion Wacholder. As we say at Pesach: if it was only for him, “it would have been enough.”

May his memory be, and it is, for a blessing.

Delivered at HUC-JIR Board of Governors Meeting, 13 June 2011, New York, NY.

(13) Thoughts from James Bowley nearing Ben Zion Wacholder’s First Yartzeit

I wanted to send you a few remembrances of Ben Zion Wacholder, as his yahrzeit is approaching. I was a student at HUC from 1986 to 1992 and then stayed in Cincinnati and worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls project with Marty Abegg and him until 2005. Looking back, I am so grateful that in spring of 1987, John Reeves, who also worked for Ben Zion, asked if I would like to join him in being a student research assistant. I now see that saying ‘yes’, radically changed and enriched my life.

I offer to you these fragments of my memories of him, whom I admired and loved, in addition to my words to the Board of Governors of HUC, which you already have.

When I was a student, I would often give Ben Zion a ride home on the afternoons that I worked for him. One time shortly after we had left HUC, I started talking about how he had such a knack for filling in the gaps/lacunae in Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts, which he often did in compelling ways. Of course, this was because he knew so much of Jewish literature and had such a keen mind that he had a superb instinct for knowing what ‘ought’ to be written in the gaps. But as we talked about it that day, he said (and I remember that we were just approaching Central Parkway on Dixmyth Ave), “My whole life I’ve been filling in lacunae.” He was quiet then, and so was I.

Everyone who knew him at HUC will probably remember that he seemed always to be chewing a rubber band, at least whenever he was in his office or the hallway. I never had the nerve to ask why. Did he not like gum? Were they just so much cheaper than gum or better somehow? Did he like the taste or feel? I have no idea, but it still makes me smile.

HUC folk will also remember how he could so often be found walking up and down the stairwell in the Klau Library Building. I’m sure he was thinking and ruminating as he ascended and descended it seemed for hours. Sometimes it was a good place to ask him a question, but sometimes he just kept moving, so if you wanted your question answered, you got some exercise too.

And, of course, he was famous for getting exercise, running all over the streets of Roselawn and farther afield, despite his poor eyesight. I remember Toby asking me to go look for him one time, and more than one of us worried that the call would come one day that he had been hit by a car. He proved us all wrong.

When I worked for him during the summers, I would go to his house in the morning usually one day a week and work until mid-afternoon. Those were days of amazing work (on his part) and trying to keep a nose above water (on mine). They were full of questions and trying to find answers, or better, trying to find relevant sources and evidence and never going with easy (or obvious) answers. We would stop at lunch time and he would take me out to eat. We would walk either to Marx’s Hot Bagels or Tillie’s Restaurant, where we’d usually get the blintzes. I remember those walks fondly.

Because of him, I attended an Orthodox Shul for Yom Kippur for the first time. He didn’t know I was there, but I remember him being called to the bima and ‘reading’.

I only remember (more or less!) one joke that he used to tell. It was about the Shaw of Iran, who was looking to hire a new minister for his cabinet. Everyone was amazed at his open liberality, for he interviewed a Jew, a Christian, and an American. After many days of excellent interviews-all of them being highly qualifed-guess whom he hired? His nephew. I relate this joke to his impulse to not go the easy way, the seemingly obvious way, for answers. Answers might lie in directions that no one has even mentioned yet. And life itself, for good or ill, may go down paths never imagined.

And finally, from my personal journal, a short entry.

15 May 2006

Spoke with Ben Zion for about 5 minutes today.

Told him (reminded) of my conversion and what I tell people when they ask me why I converted. “Because I’m Jewish” I say.

“I love you” he told me.

And, as usual, he was eager to move on and get off the phone.

As you know, Ben Zion was beloved by many, and I just wanted you to have these reflections in case they add a little more to your blessed remembrance of him.

Published Obituaries

(1) HUC-JIR Mourns Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, z”l

Freehof Professor Emeritus of Talmud and Rabbinics at HUC-JIR/Cincinnati

Professor Ben Zion Wacholder, scholar of Talmud and Rabbinics, began his career at HUC-JIR as the Los Angeles School’s first librarian in 1956. His early work in the burgeoning library collection helped usher the new school into accreditation — the committee that came to evaluate the campus cited his presence in the library as their reason for support.

Born in Ozarow, Poland in 1924, Wacholder studied in European yeshivot and was recognized as a scholar in Europe before World War II began. In October 1942, the Nazis liquidated his town, but Wacholder survived the Shoah, living as a Christian under an Aryan name and working in a Polish labor camp until liberation. After the war, he moved to Paris and later Bogota, Colombia, and finally immigrated to the United States in 1947 with the goal of resuming his education.

Wacholder received his rabbinical ordination from Yeshiva University in 1951 and his Ph.D. from UCLA in 1960. Soon after joining the HUC-JIR staff, he became a permanent member of the College-Institute’s faculty, ultimately being named the Solomon Freehof Professor of Talmud and Rabbinics in Cincinnati, where he taught until his retirement. Wacholder’s students speak of the warmth and magnetism that drew them to their teacher, a brilliant Talmudist who knew scripture and rabbinic texts by heart. When his eyesight deteriorated in the 1970s, dozens of his rabbinical and graduate students flocked to assist him with his research.

Martin Abegg (now co-director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute at Trinity Western University in British Columbia) describes the experience of working “knee to knee” with his mentor: “I have often thought that my 5 years with Ben Zion Wacholder — in the hands of a gifted writer — would rival Mitch Albom’s Tuesday’s with Morrie. Only with me it was Tuesdays and Thursdays with Ben Zion. I, in the rich company of a dozen other HUC-JIR grad students over the years, was Ben’s eyes.”

The students would open mail from scholars around the world seeking his input on scores of topics and would lend their sight to Wacholder’s study of secondary sources in multiple languages. They were constantly awed by their teacher’s flawless knowledge of primary text. Wacholder imbued his students with the lesson that as helpful as modern technology might be, a computer search engine can never replace personal knowledge of the Bible, Talmud, Midrash, and all of the commentaries that create our layered text.

Abegg co-authored Wacholder’s seminal work, an unauthorized edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls, titled A Preliminary Edition of the Unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls (Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991). Together they developed a computer program that reconstructed fragmented sections of the scrolls from a concordance, thereby making the full content of the scrolls accessible and leading to the release of the original manuscripts, which had been withheld from the public for years.The work opened wide the study of the scrolls to new scholars, leading to the establishment of the Dead Sea Scrolls Foundation to raise funds for research and preservation.

Abegg notes that the legal writings in the Dead Sea Scrolls “provide a critical window into the shape of Judaism before the Mishna and the [Jerusalem and Babylonian] Talmuds.” Professor Wacholder “realized this potential” and made it accessible to the academic community. Abegg and another former Ph.D. student, Tim Undheim, are currently putting the finishing touches on Wacholder’s latest work, The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Brill 2006). Abegg concludes: “My adventure with Ben Zion was priceless. This is the kind of education that all of us hope for from our schooling but few of us actually experience.”

[From The Chronicle, Issue 68]

(2) Remembering Rabbi Wacholder, professor emeritus of Talmud, Rabbinics at HUC-JIR, from The American Israelite

Rabbi Ben Zion Wacholder, professor emeritus of Talmud and Rabbinics at HUC-JIR in Cincinnati, who held the Solomon B. Freehof Professorship of Jewish Law and Practice, died peacefully at home in Roslyn Heights, N.Y., on March 29, 2011, at age 88, after a long illness.

Born in Ozarow, Poland, Rabbi Wacholder studied at the Baranovitch Yeshiva in Lithuania before World War II began. In October 1942, the Nazis liquidated his town, but Wacholder survived the Shoah, living as a Christian under an Aryan name and working in a Polish labor camp in Germany until liberation. After the war, he moved to Paris and later Bogota, Colombia, and finally immigrated to the United States in 1947 with the goal of resuming his education.

He received a B.A. in English at Yeshiva University and he was ordained at Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary He received a Ph.D. in history at UCLA.

Professor Wacholder began his career at HUC-JIR as the Los Angeles school’s first librarian in 1956. His early work in the burgeoning library collection helped usher the new school into accreditation — the committee that came to evaluate the campus cited his presence in the library as their reason for support.

Dr. Wacholder’s specialties were the origins and development of Talmudic Judaism and ancient Jewish commentaries, and he played a key role in enhancing scholars’ access to the Dead Sea Scrolls. He trained generations of Reform rabbis and other scholars at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. The author of many scholarly papers and several books, his most recent was The New Damascus Document: Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Martin Abegg, co-director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute at Trinity Western University in British Columbia, described the experience of working “knee to knee” with his mentor, Professor Ben Zion Wacholder: “I have often thought that my years with Ben Zion Wacholder — in the hands of a gifted writer — would rival Mitch Albom’s Tuesday’s with Morrie. Only with me it was Tuesdays and Thursdays with Ben Zion. My adventure with Ben Zion was priceless. This is the kind of education that all of us hope for from our schooling but few of us actually experience.”

Abegg co-authored Wacholder’s seminal work, an unauthorized edition of the Dead Sea Scrolls, titled A Preliminary Edition of the Unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls (Biblical Archaeology Society, 1991). Together they developed a computer program that reconstructed fragmented sections of the scrolls from a concordance, thereby making the full content of the scrolls accessible and leading to the release of the original manuscripts, which had been withheld from the public for years. The work opened wide the study of the scrolls to new scholars, leading to the establishment of the Dead Sea Scrolls Foundation to raise funds for research and preservation.

When Professor Wacholder’s eyesight deteriorated in the 1970s, dozens of his rabbinical and graduate students flocked to assist him with his research. They would open mail from scholars around the world seeking his input on scores of topics and would lend their sight to Wacholder’s study of secondary sources in multiple languages. The students were constantly awed by their teacher’s flawless knowledge of primary text. Wacholder imbued his students with the lesson that as helpful as modern technology might be, a computer search engine can never replace personal knowledge of the Bible, Talmud, Midrash and all of the commentaries that create our layered text.

“When I was a student at HUC, it was well before the Internet era. In my senior year I took an advanced, Hebrew-language seminar in intellectual history and we came across a term that no one in the class knew, including the professor. I announced to the class that though I did not know the meaning of the term, I guaranteed I would find out and report back to the class at the next session. The next week I indeed came back with the correct translation. “How did you find out?” the professor asked. “I asked Dr. Wacholder,” I replied. Ben Zion Wacholder was my Google before Google was invented,” commented Rabbi Charles Arian, of Norwich, Conn.

“While the biblical David slew a giant, this David has stood on giant’s shoulders. There are a few giant figures that come into one’s life. Dr. Wacholder was one of those giants for me. His prodigious mastery of primary texts are well known, and separated him from his peers. I think that a scholar of his magnitude only comes around once in a lifetime and he will be remembered for generations to come in the world of academia,” remembered David Maas, Ph.D., assistant professor of Old Testament at Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary.

Wacholder’s first wife, Touby, died in 1990. His second wife, Elizabeth Krukowski, died in 2004.

Rabbi Wacholder is survived by four children: Nina (Robert Goldenberg), Sholom (Michelle Rhone), David (Chana Sara), and Hannah (Daniel) Katsman; and 15 grandchildren.

Dr. Wacholder was buried at Eretz Hachaim Cemetery in Bet Shemesh, near Jerusalem.

Source: The American Israelite, May 11, 2011

View the online edition here (May 12, 2011 edition)

(3)An Obituary by Michael A. Meyer, Adolph S. Ochs Professor of Jewish History, HUC-JIR/Cincinnati

A long-time Fellow of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Ben Zion Wacholder passed away in Roslyn Heights, New York, on March 29, 2011, at the age of 86. He had been the Solomon B. Freehof Professor of Talmud and Rabbinics at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR) in Cincinnati and a major figure in the study of ancient Jewish history, especially of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Born in Ozarow, Poland, Wacholder studied at the Ohel Torah Yeshivah in Baranovitch in what is today Belarus and was soon recognized as a brilliant Talmud scholar. His life took a sharp turn when the Nazis destroyed his town in October 1942, forcing him to seek survival under a false identity. Living under an invented name and disguising his Jewishness, he worked in a Polish labor camp and hid in forests until liberation. He then moved to Paris, to Bogota, Columbia, and finally to New York in 1947, where he received rabbinical ordination and a B.A. in English literature from Yeshiva University. He went on to graduate studies in ancient history at UCLA, where in 1960 he obtained a Ph.D. with a dissertation that became his first published book, Nicolaus of Damascus (1962).

He joined the newly established Los Angeles branch of HUC-JIR as a librarian while still a graduate student in 1957 and was soon appointed to its faculty. In 1963, Nelson Glueck, president of HUC-JIR, asked Wacholder to join the faculty in Cincinnati, where he remained until his retirement.

Although principally teaching courses in Talmud and rabbinic literature, his field of specialization remained the ancient world, exemplified by Eupolemus: A Study of Judaeo-Greek Literature (1974) and Essays on Jewish Chronology and Chronography (1976). Beginning in the late 1970s, he increasingly concentrated his scholarship on the Dead Sea Scrolls, producing in 1983 The Dawn of Qumran: The Sectarian Torah and the Teacher of Righteousness, in which he argued that the Temple Scroll was intended to be nothing less than a new Torah to replace the Mosaic one at the End of Days. He also published some four dozen articles, mostly devoted to the Scrolls.

Wacholder gained broad international attention when, disturbed by the failure of the committee in charge of the Scrolls to make them public, he, together with a graduate student, Martin Abegg, reconstructed and published the presumptive text of the unpublished material from Cave 4 on the basis of a concordance that indicated the place and context of the words that it listed. The text appeared in fascicles beginning in 1991 as A Preliminary Edition of the Unpublished Dead Sea Scrolls: The Hebrew and Aramaic Texts from Cave Four. The reconstruction proved to be nearly 100% accurate and broke the monopoly of the international committee that had kept the text secret for decades.

Wacholder’s scholarship, especially late in his career, was nearly always controversial, even as it was serious and stimulated debate. He was rarely satisfied with conventional views, arguing, for example, that the Teacher of Righteousness and the Wicked Priest mentioned in the Scrolls were not historical but, rather, eschatological figures who would appear at the End of Days. He attended scholarly conferences regularly, eager to advocate for his theories among his colleagues.

At HUC-JIR Wacholder taught both rabbinical students and Christian graduate students, whose Doktorvater he became. He was known as a kind and thoughtful teacher, who encouraged students even as he challenged them not to rely on secondary literature or conventional interpretations, but to analyze the primary sources first and foremost and to seek their own conclusions. As his eyesight progressively deteriorated, he continued his scholarly work and his teaching, causing students to marvel at how he was able to recite texts that he could not see but could draw upon from the storehouse of his prodigious memory. In 1994, two of his graduate students, John C. Reeves and John Kampen, presented Wacholder with Pursuing the Text: Studies in Honor of Ben Zion Wacholder on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday. Still in 1996, when he could barely see at all, two students helped him put together his The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls. As late as 2007, he was still able to publish The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah: Reconstruction, Translation, and Commentary.

Ben Zion Wacholder was a generous man who never refused a contribution to the poor and who gave freely of his time to anyone who wanted to study with him, often in his own home. Though he taught at a Reform seminary and cherished freedom of thought, he was personally a fully observant Jew. As his eyesight grew worse, he continued to study and write, using a specially adapted computer and the services of students who would read the material to him. Late in life, his cognitive faculties, as well, began to fail, but he could never rest from intellectual endeavor. He was a devoted father and grandfather. Wacholder’s first wife, Touby, died in 1990, his second Elizabeth Krukowski in 2004. He lived the last years of his life with his daughter Nina in Roslyn Heights. He is survived by four children and fifteen grandchildren. He was buried, as he wished, in the Land of Israel.

[From AAJR.org/obituaries

Other Documentation

(1)Record of Ben Zion Wacholder’s departure for South America

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee recently released its archives, including the official record of Ben Zion Wacholder’s departure from Barcelona to Colombia:

Source: JDC Archives

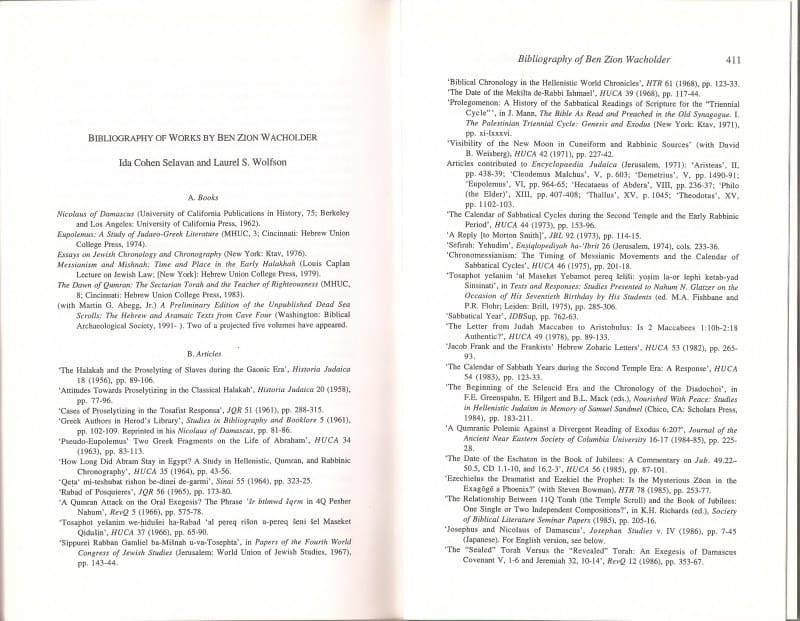

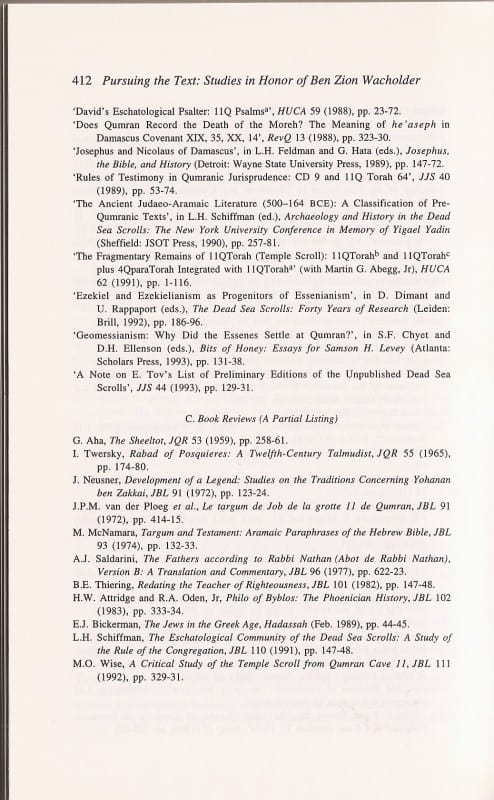

(2) Bibliography of works by Ben Zion Wacholder, from Pursuing the Text: Studies in Honor of Ben Zion Wacholder on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday

John C. Reeves and John Kampen, 1994, Sheffield Academic Press

Reproduced by kind permission of Continuum International Publishing Group

Portions of the text can be viewed online here

Works published since 1994:

The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Reconstruction, Translation and Commentary (The Netherlands: Brill, 2006)

We invite you to share your own memories Ben Zion Wacholder by sending them to BZWacholderMemories@gmail.com. This page is managed by Shifra Goldenberg, Rabbi Wacholder’s granddaughter.